Unnatural disasters and the myth of Filipino extraordinary resilience

The way nature works has always been shrouded with mystery. How are tsunamis formed? Are mountainous areas really susceptible to landslides? Are all disasters primarily dependent on location or is there a bigger picture that we refuse to acknowledge?

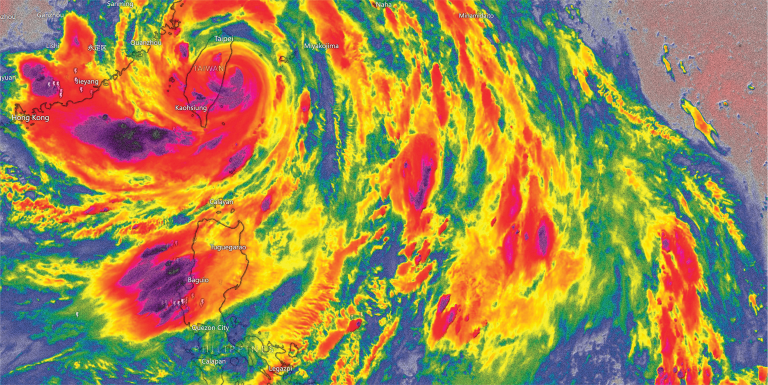

Let’s talk local. The Philippines is situated in the Northwest Pacific Basin, a region frequented by cyclones. To boot, it is also part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, infamous for its unusually high seismic and volcanic activity, rendering the region prone to volcanic eruptions as well as earthquakes.

So it doesn’t come as a surprise that the country is the most vulnerable among 103 countries in terms of exposure to natural hazards and disaster risks, according to the World Risk Index. Equally alarming, a paper from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that “60% of the Philippines’ land area and 74% of its population are exposed to numerous hazards, including floods, cyclones, droughts, earthquakes, tsunamis, and landslides.”

Even without all these statistics, weathering catastrophes is commonplace in the Filipino consciousness, an experience that everyone in the country is surely no stranger to. Unfortunately, this trend is not going away and threatens to only go down a slippery slope if not appropriately mitigated.

As the climate crisis looms, the frequency and strength of typhoons threaten to increase in the coming years. A report penned by United Nations (UN) Resident Coordinator in the Philippines Gustav Gonzalèz details how climate change already affects communities, with the 2024 typhoon season proving to be a recent instructive example of what is to be. The IMF also predicts that damages to infrastructure and communities just in 2024 cost around 1.2% of the country’s GDP, translating to about PHP 318 billion. This is projected to increase to up to seven percent by 2030 due to climate change.

Redefining disasters

“Natural” disasters are often earmarked by their occurrence and intensity, each occurrence is compared with the previous one.

Environmental geographers have been lobbying for a certain truth–that disasters are no longer “natural,” as time changes. They posit that the impacts of these disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons are aggravated by social systems and human behavior.

The 2024 Standard Operating Procedures and Guidelines (SOPG 2024) of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Operations Center states that the term ‘hazard’ is more applicable to the Philippines’ current situation. A hazard, in this light, is a dangerous phenomenon, substance, human activity or condition that results in the loss of life, injury, or other health impacts, damage to property, loss of work and services, and economic turbulence and environmental damage.

Furthermore, hazards may either be natural or anthropogenic. In 2024, a whopping total of 1489 human-induced hazards were documented in the Philippines. Some of these hazards included vehicular accidents, forest fires, and localized storms.

In contrast, a disaster is defined as “a result of an extreme event.” This begs the question, what transforms a hazard into a bona fide disaster?

Disaster in the making

Substandard infrastructure, lack of updated and preventive measures, and dysfunctional politics. These are all contributing factors as to why disasters, despite being known and foreseeable at times, still result in record-breaking numbers when it comes to damages, losses, and most importantly, lives.

The misappropriation of flood-control funds by incumbent government officers and officials have recently been exposed. What was supposed to be for the construction of flood-control projects was pocketed and spent by several public officials and officers for their personal gain.

Typhoons are expected in the Philippines due to its climate; however, the destruction of properties, the loss of lives, and the lack of access to basic utilities is not normal, nor should it be accepted as a consequence because they could have been prevented in the first place.

It is clear that this will be a persistent problem in Filipino society. But how do we mitigate these risks and respond appropriately?

At the heart of disaster and risk management are the people

“A holistic disaster risk management approach starts with a change in the way we refer to disasters,” writes the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). “When the damage and loss caused by a disaster is declared ‘natural’ or ‘act of God,’ communities and governments are absolved of their responsibility.”

Recent scandals involving corruption in government have led to chronic neglect and mismanagement of public infrastructure and recurrent flooding disasters across the nation’s capital. These issues recently compelled widespread massive protests across the country, demanding accountability from those in positions of power. But how responsible exactly are governments?

The Sendai Framework, established at the 2015 UN World Conference for Disaster Risk Reduction, enforces member states to create policies that substantially attenuate “disaster risk and losses in lives, livelihoods and health and in the economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets of persons, businesses, communities and countries.” This comprehensive agenda also comes with a suite of initiatives that aims to address and buoy the effects of the climate crisis, including the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, and the larger compass being the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals. The Sendai framework critically places state governments at the nexus of responsibility to enact disaster risk reduction measures.

Despite the Philippines’ history with natural hazards, the institutionalization of disaster risk reduction is surprisingly relatively recent. Republic Act 10121, formally known as the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act, established what we currently know as the National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Council (NDRRMC) only in 2010. This law, signed in the 14th Congress, laid out an exhaustive framework for the government’s approach at mitigating disasters, effectively formulating a more proactive policy for disaster management, focusing particularly on risk reduction.

Chairing this council is the Secretary of Defense (DND), with various secretaries of executive departments as vice chairs. Each vice chairperson functions to serve toward thematic pillars of the overall disaster risk management strategy: Department of Interior and Local Government for disaster preparedness, Department of Social Welfare and Development for disaster response, Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for disaster prevention and mitigation, and the National Economic and Development Authority for rehabilitation and recovery. This document envisions a country with “safer, adaptive, and disaster-resilient Filipino communities toward sustainable development.” This law promulgated the formation of a central document known as the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plan (NDRRMP), collaboratively put together by the NDRRMC to orchestrate an organized response towards hazards. The latest version of this was implemented in 2020 under the Duterte administration, known as NDRRMP 2020-2030, involving what was described as a “whole-of-society” approach emphasizing bottom-up, community-based policies on disaster response with feedback and lessons from major disasters in the past, including typhoons Yolanda, Ondoy, Pablo, Sendong, and more.

A salient portion of this document incorporates environmental management into risk reduction—emphasizing the importance of protecting natural resources from degradation due to human activities such as deforestation and coastal mismanagement. The document also urges proactive policies such as avoiding faulty agricultural practices like monocropping, which has been proven to impede recovery in disaster-stricken areas. Another important emphasis was on data and knowledge management, with a recent example being the crowd-sourced OpenStreetMap, a technological joint initiative by government, industries, and the academe that resulted in more effective coordination and evacuation particularly during typhoon Sendong.

A rather infamous example in the document puts concise risk communication at the center of disaster response. The term “storm surge” was paraded around to forewarn communities in the advent of typhoon Yolanda, but to no avail as this was not a familiar term among the communities and thus, held almost no meaning. This resulted in faulty evacuations and the eventual tragedies that the southern provinces suffered heavily from. This highlights the vital part technology and communication strategies play in disaster management and enforces these organizing principles into government responses.

Additionally, the updated framework includes hazards such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which it says exposed large gaps in systems, and thus demands capacity-building in terms of community-based health practices, infrastructure as well as livelihoods and economy, what’s termed as an “all hazards and resilience framing.”

This updated NDRRMP framework generally drives a more climate-sensitive and scientifically informed agenda for the government—both at the national and local level—to respond to disasters and effectively equips the country with a comprehensive plan of action.

Where are we now?

In conjunction with the Sendai Framework that centers more on disaster preparedness than response, the new NDRRMP covers four thematic areas to address hazards and disasters. These are prevention and mitigation; preparedness; response and early recovery; rehabilitation and recovery. In other words, this policy is hinged on disaster resilience being an active ingredient to capacity building and not simply an afterthought.

One of the most salient parts of this document activated in the event of disasters are informational platforms that are utilized for information dissemination as part of resilience. GeoRisk Philippines is one of these platforms, a multi-agency initiative spearheaded by Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology with collaborations between Department of Environment and Natural Resources, DND, and DOST. As a geospatial information platform, GeoRisk PH enables users to look at hazard maps in their specific communities. This open source algorithm conducts a hazard assessment that informs users on hydrometeorological (i.e. typhoons), volcanic, and seismic (i.e. earthquakes, landslides) hazards. More importantly, it also provides information on critical facilities that are most proximal and necessary in cases of calamities, including the nearest evacuation centers, secondary roads, primary roads, and health facilities.

Other platforms for disaster information dissemination include the NDRRMC logistics management system dashboard as well as PhilAWARE. Another interesting part of this document entails more progressive approaches to disaster responses, like integrating gender and cultural responsiveness in the response measures as well as financial structures that enable the dissemination of emergency cash transfers in the event of disasters. Most critically, the NDRP document also highlights several concrete protocols as well as situational triggers for responses for specific hazards—designating the roles of different clusters—from national agencies to local government units such as barangays—in both preventing and actively responding to disasters.

Not surprisingly, the document reports on how implementation across sectors is still a considerable barrier. If we are to take disaster response seriously, it is imperative that the government at its every level fall under this unified proactive, disaster prevention framework. Leading agencies should prioritize quality control as an agenda to audit local government’s adherence to these policies down to its most basic units and grassroots as this is where disaster response begins. This also applies to other elements of society across different sectors—including citizenry—to raise awareness and ensure action-based agendas toward disaster preparedness.

In 2025, further measures have been enacted toward disaster response in the country, not least of which is a PHP 1 Trillion national budget allocation on disaster resilience “to combat climate change and promote sustainable development.”

A “carbon credit policy,” spearheaded by the Department of Energy and in partnership with the Singaporean government is also in the works, that seeks to incentivize carbon emission cuts “through clear rules that drive private sector participation in clean energy and decarbonisation efforts,” an article from Argus media writes. Argus is a leading provider of global energy and provides market insights on petroleum, natural gas, and renewable energy.

Recent Philippine legislation has also put disaster response in the center, with the final reading of the state of imminent disaster bill in Congress. An article from Resilient.ph writes, “This innovative measure would authorize a preemptive declaration of an “imminent disaster” based on scientific forecasts, facilitating the immediate mobilization of resources, in contrast to the existing process of declaring a “State of Calamity” after a disaster has occurred.” Indeed, “if enacted, the Philippines would become the first country in the region to legislate anticipatory action.”

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. earlier this year in April has also signed RA 12180, otherwise called the PHIVOLCS Modernization Act, which seeks to enhance the scientific capacities of the agency for better responses against seismic hazards.

Dismantling the myth of Filipino ‘resilience’

Measures to enhance disaster response are clearly in place in the grander scheme of Philippine legislature and political architecture. However, resilience has long been framed as an individualized responsibility, what with the frustrating amount of media and news cycles that focus on the Filipino attitude of “resilience” in the face of catastrophic adversity, giving room for government neglect and abuse. This is exemplified no less by the recent flood control scandals that drain the nation’s coffers that would have been directed to disaster-resilient infrastructures and ultimately, lives saved.

It is also a tragic coincidence that, as of writing, a 6.9-magnitude earthquake recently hit the country’s central provinces, leading to more than 60 fatalities and substantial damage to infrastructure, including prized heritage sites.

“A more nuanced view of extreme events is needed,” the UN states in an article on disaster response. “In fact, it is the choices we make that cause a disaster. The earthquake might be random, but the vulnerability to damage—the risk that people expose themselves to—determines whether it develops into a disaster.”

It is our choices that bring upon disaster. In this vein, no disaster is natural. The majority of blame lies with government officials and political hooligans who continue to drain our coffers for personal gain. Arguably, corporations that conduct environmentally harmful practices for capital also play into this scheme. Additionally, dominant media entities that disproportionately frame disaster response as one hinged on individual resilience and “bayanihan” rather than an issue of government accountability and environmental justice.

As we face another typhoon season and a recent seismic disaster, it is perhaps time to also ask ourselves: what is the price of resilience and how much do we contribute to the mythmaking—that disasters are “natural” and that we, in turn, are resilient people?

Our country’s troubled history might have weathered many odds, but let us not establish this as an easy cop out for governmental neglect, personal greed, and environmental sacrilege. It is high time to bust this myth and demand more accountability from those in power. We can no longer allow ourselves to be limited to a response when the hazards we have been suffering through could have been prevented or mitigated through proper planning, information dissemination, and maximization of systematic resources.

At the core of every misfortune that our country and countrymen has faced, lies resilience. Resilience has always been related to temporary struggles and how we all move forward together; resilience has become tolerance. It has been for the longest time.

Now, whether by fire, wind, or rain, resilience can mean, “we’ve had enough.”