Are the storms of today stronger than the storms of yesteryears?

With the noticeably higher temperatures we experienced this summer, does the escalation of climate change mean that this year’s typhoon season will be worse as well?

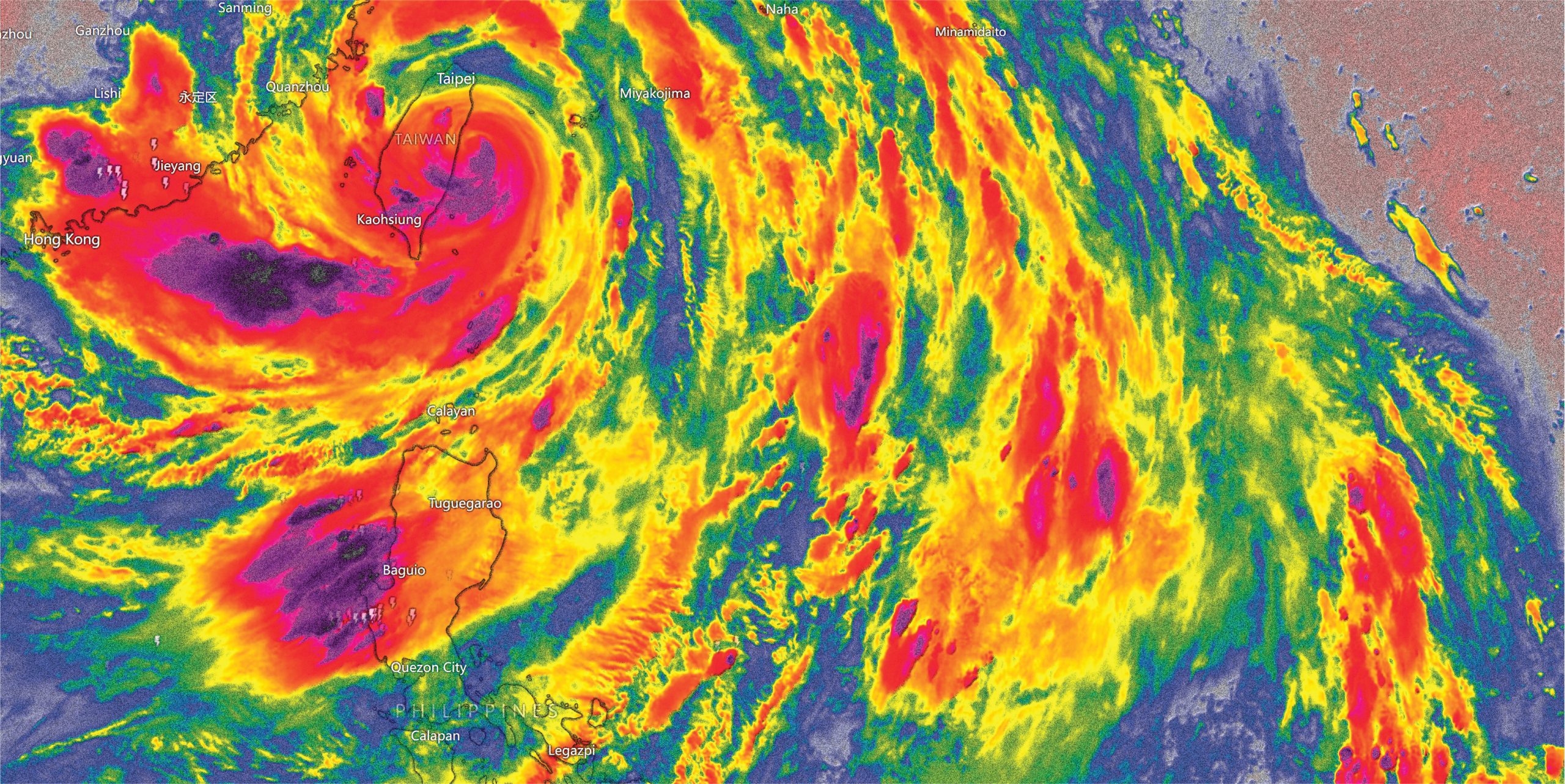

The Philippines is no stranger to devastating storms. Its location along the Pacific Ocean’s typhoon belt makes it geographically inclined to experience torrential downpours at high wind speeds nearly every year. Filipinos are known for making the most of this bad situation, keeping a good sense of humor despite the weather and coming together to deal with the eventual aftermath, but recently people have been noticing a rather ominous trend and can’t help but wonder: are typhoons getting worse? Why does every video of a storm or flood posted to social media look worse than the last? And where does this leave us, if today’s storms are already leaving dozens of casualties in their wakes?

A team of scientists from UP Diliman’s Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology (IESM) decided to tackle these uncertainties by studying the physical properties of extreme weather events, such as typhoon Ulysses (Vamco) of 2020, and running computer simulations to answer the question: “What would Ulysses have looked like 40 years ago on a cooler planet?”

Turning back the clock

Helmed by Dr. Gerry Bagtasa, the team used the Pseudo Global Warming or PGW method to recreate a storm like Ulysses in the climate conditions of a different time. The PGW method can be used to characterize a storm’s intensity, size, rainfall, and wind exposure. For Bagtasa’s purposes, the most important of these variables is intensity, which describes the strongest winds of a tropical cyclone, and is actually how these storms are categorized. Rainfall is another important variable, which Filipinos know all too well often leads flooded streets and waterlogged homes. Together, most of the damages caused by tropical cyclones stem from these two hazards: wind and rain.

Forty years ago, the ocean temperatures were around 1.6 degrees cooler than today, which doesn’t sound like much, but can have a massive effect on the strength of weather phenomenon like typhoons. Based on Bagtasa’s research, Ulysses would have been 15% less intense if it had happened in 1981, when global warming was not as prevalent as it is today. It would have still been intense, with maximum wind speeds of approximately 130 kph, but decidedly less intense than the 155 kph winds we experienced in 2020.

The team’s research also allowed them to bring storms of the past to the present. It’s difficult to imagine how historic storms, such as super typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in 2013, could get worse, but Bagtasa’s research shows that, if a storm that intense were to happen today, it would be even more devastating and deadly.

Rising temperatures, rising stakes

A small silver lining is that, while storms become more intense due to rising ocean temperatures, global warming is causing ambient and environmental temperatures to rise as well, acting as a sort of counter force to the ocean temperatures and lessening today’s storms’ potential intensity. However, Bagtasa warns that this should not make us complacent.

“Rising ambient or environmental temperature has its own various negative consequences. For one, we will have extreme heats especially during the hottest months of the year (Mar-Apr-May). [In addition to its effects] on people, higher temperatures are also affecting plants as well as animals.” He adds, “Overall climate projections tell us that there will be less tropical cyclones in a warmer world, but those that do form will be more intense.”

A port in the storm

Natural disasters like hurricanes and floods caused by global warming can make anyone feel powerless. After all, what can any of us do in the face of something that affects everyone on a global scale? Bagtasa suggests the most we can do is mitigate the damage by sharpening our knowledge and understanding of these phenomena. Better science communication skills will lead to people being better prepared for what is to come.

In an article written by Andre DP Encarnacion for UP Diliman, Bagtasa cites the concept of “landfall” as one people should better understand. “Landfall indicates that the eye of the storm has moved over land,” Bagtasa explains. “One of the mistaken impressions is the idea that you will only be affected by a typhoon when it makes landfall. But a typhoon is not just a single point! It is hundreds of kilometers wide. So even without making landfall, it can actually have an effect, and a devastating one at that.”

When asked what other concepts people should be more aware of, Bagtasa adds, “Another very important aspect to understand is the uncertainties involved in weather forecasting. The science of weather forecasting is not perfect, there are still a lot of things that we don’t understand completely and that limits our ability to forecast weather.” With this in mind, it’s best to be as prepared as possible, especially during typhoon season. Keep an eye on weather reports, and know that, with typhoons predicted to worsen in intensity, one’s ability to understand these forecasts can play a vital part in weathering the oncoming storms.