Environmental pollution post-halalan and the cost of a familiar face

A month after the 2025 Midterm Elections in the Philippines, streets, trees, and walls are yet again covered in trash—previous campaign paraphernalia—that overwhelm both the people and the environment.

Ecowaste Coalition, an environmental watchdog, remarked that during the campaign and election season, the Philippines struggles with waste management due to the increasing amount of waste generated during campaign activities.

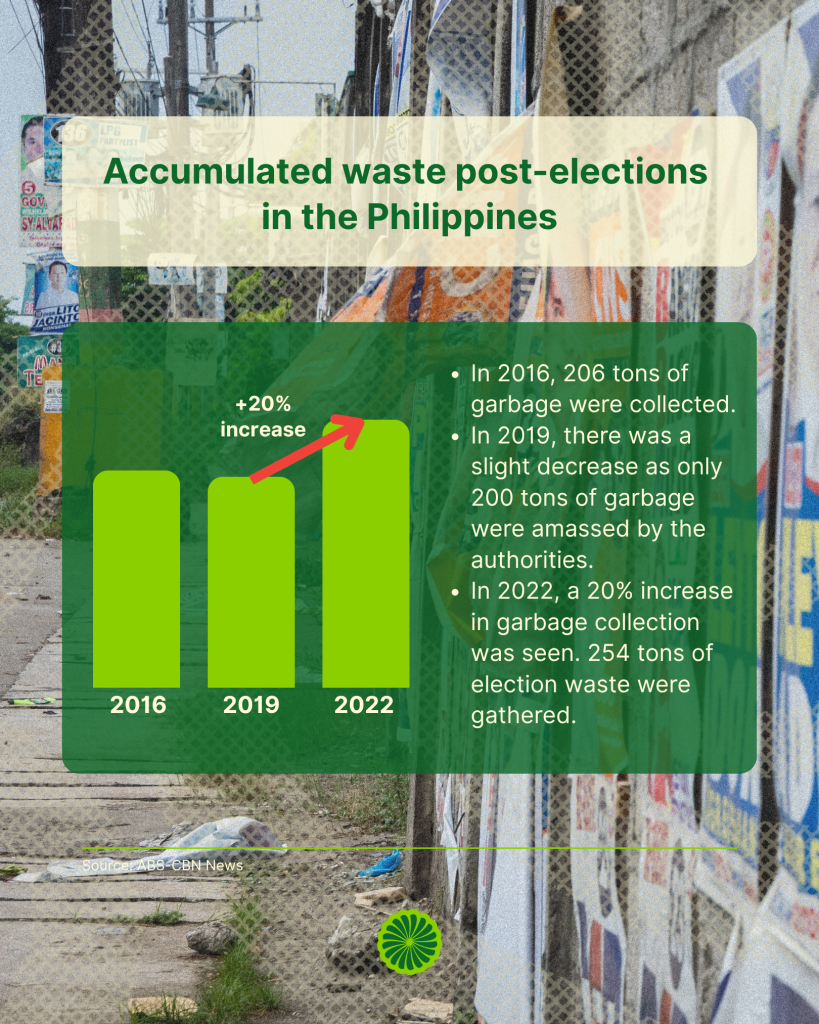

Back in the 2016 national elections, a whopping 206 tons of garbage were collected. Then 2019 saw a slight decrease to 200 tons of garbage. That’s still a massive amount of waste. To put things into perspective, a grand piano weighs about half a ton on average, while 200 tons would be equivalent to the weight of over 30 adult African bush elephants or nearly two blue whales.

Making matters worse, election waste escalated by as much as 20% in 2022, mounting up to more than 254 tons. For the National Capital Region (NCR) alone, 18 to 20 tons of waste were collected daily after the conduct of elections, the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) reported.

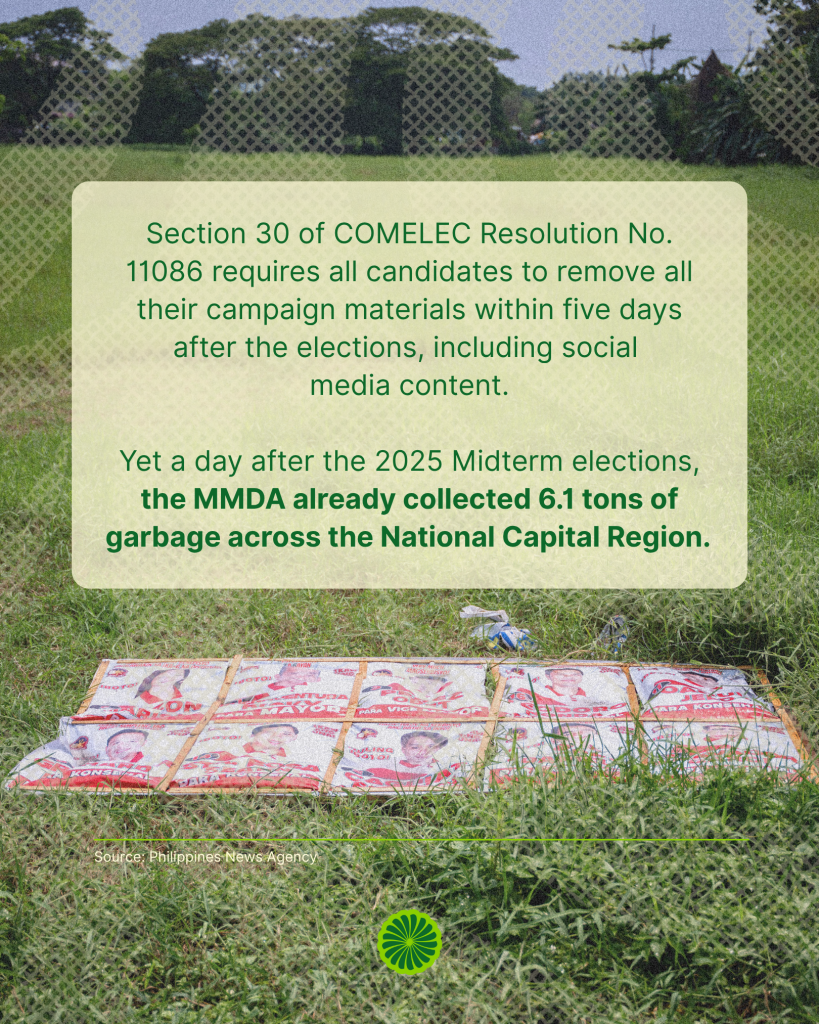

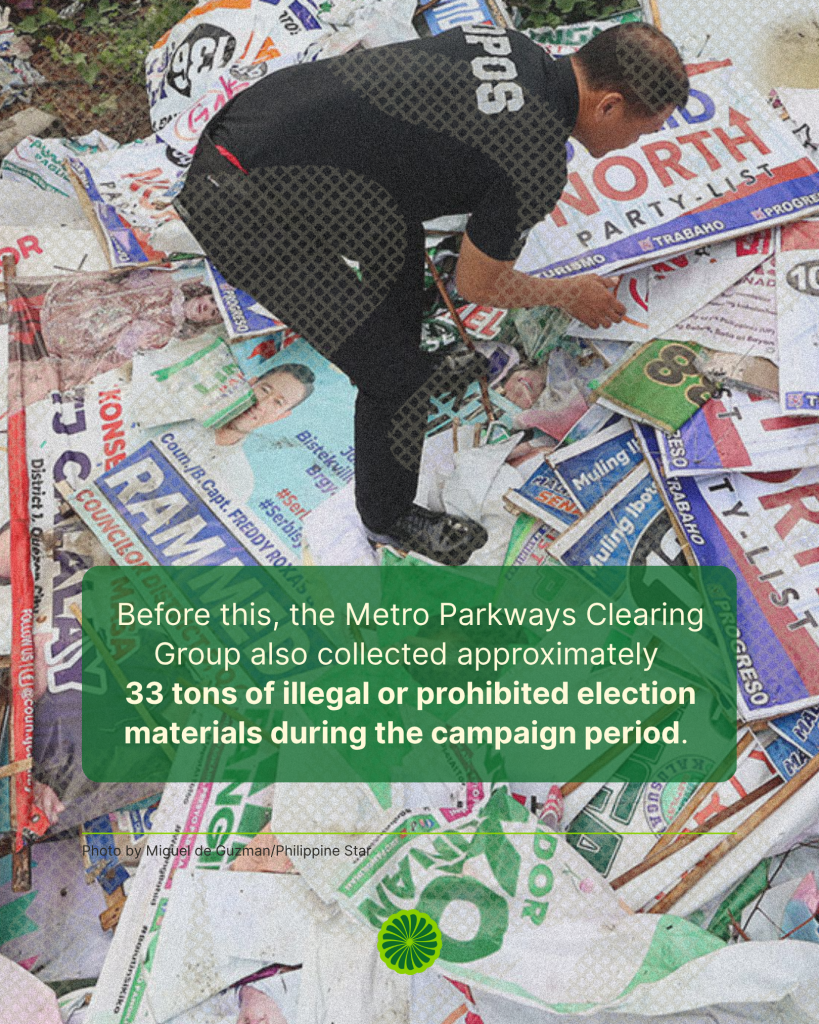

More recently, the Metro Parkways Clearing Group (MPCG) amassed approximately 33 tons of illegal or prohibited election materials during the campaign period of the 2025 Midterm Elections. On just the first day of election waste cleanup efforts, the MMDA collected 6.1 tons of garbage across NCR.

This has been the situation every election season in the Philippines and we have been asking ourselves the same question each time: will we see the end of this groundhog day?

I think we’ve seen this film before

After elections, waste materials are either disposed of or segregated for recycling. Ideally, this practice should not only occur after elections but also become customary, if not routine, for everyday waste.

However, this waste collection and segregation process faces challenges especially when it comes to determining the materials used for paraphernalia. The MMDA found some paraphernalia in the 2022 elections were made of plastics and non-biodegradable materials, specifically polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which has been associated with several health risks due to the toxins released during its production and disposal.

These mixed compositions make existing recycling and upcycling initiatives impractical and unsustainable, relegating the unusable materials to still end up in landfills.

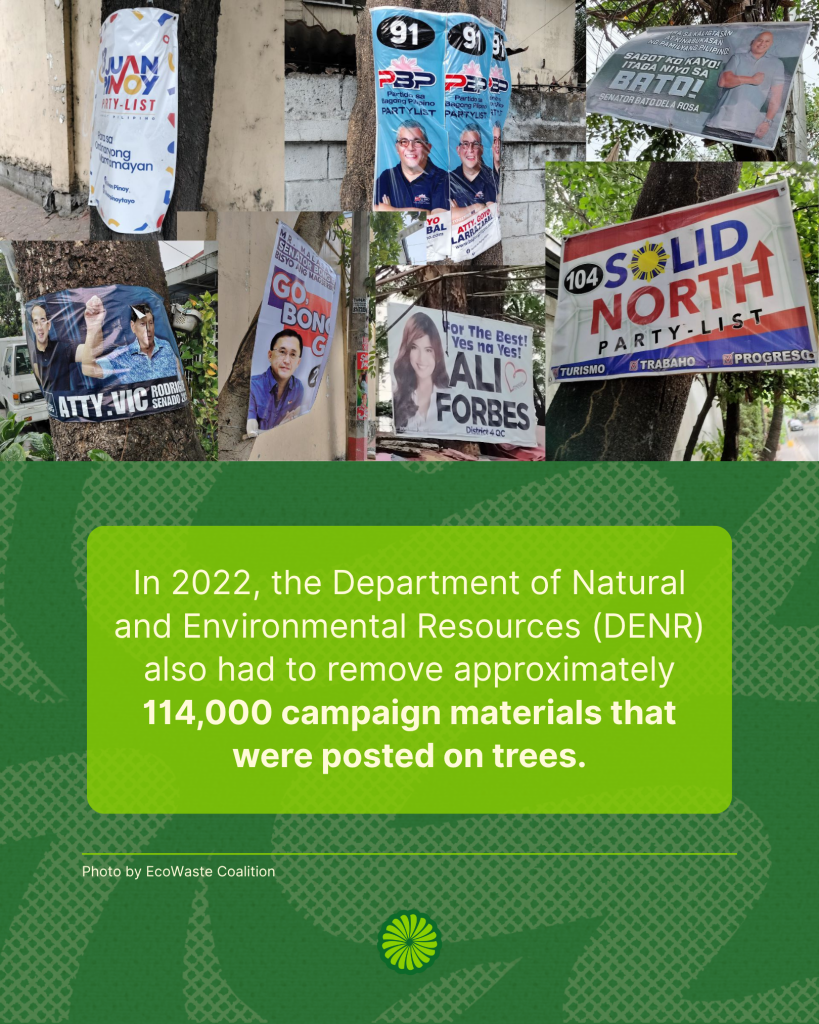

In the same year, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DENR) also had to remove approximately 114,000 campaign materials that were posted on trees. This was in clear violation of Republic Act No. 3571, which prohibits the cutting, destroying, or injuring of planted or growing trees, flowering plants, shrubs, or plants of scenic value along public roads or grounds.

Others are doing it. Aren’t the rest following suit?

When systems and sound regulations are in place, incremental efforts and improvements are seen. Indeed, selected local governments have been proactive and compliant in their clearing operations.

For example, the Quezon City government is turning a portion of its non-biodegradable campaign materials into tote bags by recycling tarpaulin materials. This is part of their “Vote to Tote” initiative, which was launched in 2022 to reduce the amount of tarpaulin materials ending up in landfills.

The Iloilo Provincial Government, meanwhile, assigned teams to properly collect and remove campaign materials across all five districts through their “Limpyo Eleksyon 2025: Operation Baklas” initiative.

These waste management practices must go beyond being labeled as post-election to-dos, but instead should serve as a reference point to develop more effective policies and implement longer-term solutions to mitigate present and pressing environmental concerns.

Post-election cleanup efforts become futile when there are no preventive means to reduce the accumulation of waste, while recent policies have been more in tune with the need to have sustainable and election practices, in actuality, proper enforcement and observance is still lacking.

While there are provisions for the violation of the guidelines and other environmental laws, there is no compass on how to encourage candidates and the general public to shift to sustainable practices in their respective ways.

Kaya today?

Familiarity is integral when it comes to a candidate’s campaign, but sometimes it becomes the sole consideration for favorable votes. Instead, may the candidate’s faces plastered around us also remind us of one of the most pressing national and global concerns of the decade—sustainability—and that our leaders must also advocate for the protection of the planet.

Post-election cleaning operations have long been required, but it is not the next best step toward sustainability and environmental protection. We need to be more involved by holding our public leaders accountable and by lobbying for more environmentally sound policies.

In 2007, the Ecowaste Coalition released a 10-point plan on how we can achieve a more sustainable elections, the plan included suggestions and measures such as assigning a point person to monitor campaign activities, discouraging the use of campaign materials that are not reusable, prohibiting vandalism or willful defacing of properties, and knowing the areas where campaign materials may be affixed.

In an interview, Cris Luage, Zero-Waste Campaigner for Ecowaste, mentioned that the cleanup operations are not merely about picking up garbage, but about setting the tone for responsible leadership.

By the same logic, perhaps it is time to rethink campaign strategies. Discourses regarding digital shifts or the use of eco-friendly materials are already being held, what’s left to do is to turn these dialogues into plans of action.

The purpose of campaigning and running for public office is to advocate for causes bigger than oneself—like this planet we live in. The more familiar their face is during elections, the more work they hopefully put into knowing the costs incurred.