Ecosystems remain collateral damage amid armed conflict

The Philippines’ ongoing conflict with the New People’s Army highlights the destructive impact of war on the environment, even long after hostilities cease.

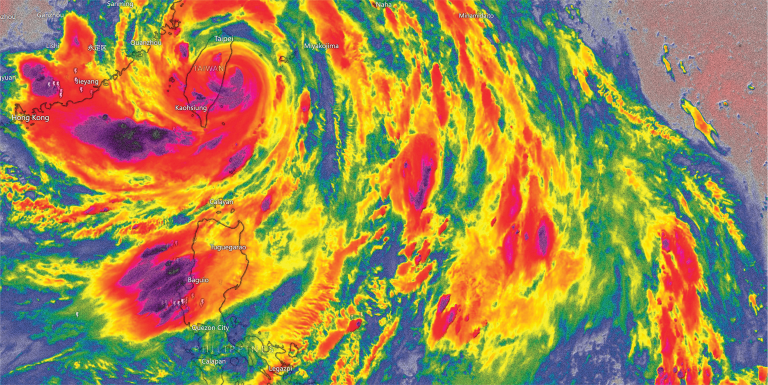

Last April 2 and 3, the communities of Pilar in Abra and Santa Maria in Ilocos Sur witnessed skirmishes between the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and guerrilla fighters from the New People’s Army (NPA). Residents were forcibly evacuated and schools were closed amid the conflict. A video capturing an airstrike by the AFP went viral, causing widespread concern.

In an interview with Rappler on April 8, Lt. Col. J-Jay Javines of the AFP claimed that airstrikes are only conducted after a particular set of conditions have been fulfilled; some of these conditions include the evacuation of residents and the guarantee of safety of “living animals”. But whether these precautionary measures are sufficient in protecting these communities, especially in the long term, might be worth questioning. For those living in Pilar and Santa Maria—where agriculture is a major source of livelihood—the consequences of violence on local ecosystems may extend beyond the resolution of conflict.

With the rising incidence of violent conflicts worldwide, their impact on the environment must be closely and consistently monitored. Military offensives affect ecosystems not only in the heat of conflict, but in all of its stages: from war preparation, when weapons testing and live-fire training occur, to the highest point of conflict, even extending until postwar reconstruction activities.

In 2019, Dr. Nelson Grima, formerly a University of Vermont researcher and now a coordinator for the Science Policy Programme of the International Union of Forest Research Organizations, and Prof. Simron Singh, who hails from the Department of Environment at the University of Waterloo in Canada, conducted case studies on four countries that had experienced armed conflicts in the last two decades. Besides direct ecological losses during active attacks, destruction to forested areas skyrocketed for an extended period of time even after the violence had settled—with the study reporting a whopping 70 percent jump in annual forest loss in the five years post-conflict.

“We identified inappropriate governance and institutional arrangements as the key driver during the transition period,” the researchers write.

Rural areas in Nepal that suffered due to conflict, for example, were abandoned by former residents as they did not receive support from their government and were unequipped to restore forests on their own. In Sri Lanka, mismanagement of forested areas was also seen after the civil war ended; although strategies for land management were designed, they were frequently revised and were not properly implemented. Similar cases were shown in Cote d’Ivoire and Peru, where corruption and industrialization negatively affected ecosystem recovery.

Depending on how the conflict develops over time, lands that turn into battle theaters may even become completely unusable and unable to recover due to compounding issues such as soil contamination, erosion, and cratering. For Grima and Singh, addressing the issue requires an adaptive co-management approach at both community and government levels.

The immediate few years after a conflict is resolved is crucial in allowing ecosystems to recover—if they are able to do so at all. The improper management of natural resources may lead to inadequate distribution among local community members and negatively impact their livelihoods. At worst, scarcity could create a greater rift between different groups, leading to the re-emergence of conflict. To help stave off these consequences, the field of “warfare ecology” may represent an important approach. Proposed by US-based scholars Dr. Gary Machlis and Dr. Thor Hanson, who both specialize in sustainability and conservation studies, the discipline primarily aims to resolve both the ecological and sociological repercussions of war, as well as “encourage the transition of former military sites to conservation purposes”.

Especially as the Philippines is a major biodiversity hotspot, it is of utmost importance for the nation to take a stance against the destruction of environmental resources in the midst of violent conflict. In post-conflict reconstruction, a comprehensive approach must be prioritized to ensure that the effects of peace are long-term; this includes the protection of biodiversity to prevent further conflict and preserve community livelihoods. Peacebuilding does not stop at the cessation of active conflict—it extends to the rehabilitation of the surrounding environment, ensuring the security of local populations, human or otherwise.