Death by plastic: Are bioplastics the answer to pervasive pollution?

The Philippines is one of the biggest contributors to plastic pollution. We can try to reduce our plastic footprint, but its practical properties simply make it impossible to eliminate from the market on a meaningful scale currently. This is why bioplastics may provide a promising alternative.

Take a look around you. There’s a very good chance that something within arm’s length of you right now is made of plastic. From phone cases, to packaged food, to polyester clothing, nearly every widely available product on the market today is at least in part made of plastic.

Depending on your point of view, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing—as a highly versatile material with low manufacturing costs, plastics make many aspects of everyday life more affordable and convenient for consumers. Single-use plastic products in particular are considered more hygienic than reusable items and are often designed with accessibility in mind. On the surface, plastic itself is something we can hardly imagine our lives without, but its effect on us and the world at large is another story entirely.

A long-term problem

Research projections show that global plastic production is expected to increase from 464 Megatons in 2020 to approximately 884 Megatons in 2050, according to a study involving De La Salle University Professors Dr. Kathleen Aviso and Dr. Raymond Tan alongside international collaborators from the European Federation of Chemical Engineers. The study, published last year in Sustainable Production and Consumption, also reports that more than half of the plastic waste generated by the year 2050 will be landfilled or mismanaged, with particularly high projected rates in industrial regions like China and North America.

Since plastic is a non-biodegradable material, every piece of plastic that has ever been made still exists in some form, and will continue to exist long into the future of our planet. To put things into perspective, it could take up to 500 long years before plastic fully decomposes. Despite this, we continue to produce hundreds of megatons worth of plastic that we as individuals may eventually throw away, but the Earth in its entirety will never be rid of.

There have been global efforts to manage the disposal of plastic in such a way that minimizes its effect on our ecosystems, but the problem persists, as an estimated 20 million tons of plastic waste leaked into the environment in 2020. This number is expected to grow by around 50 percent in the next 20 years unless more stringent waste reduction policies are put into place and implemented on a global scale.

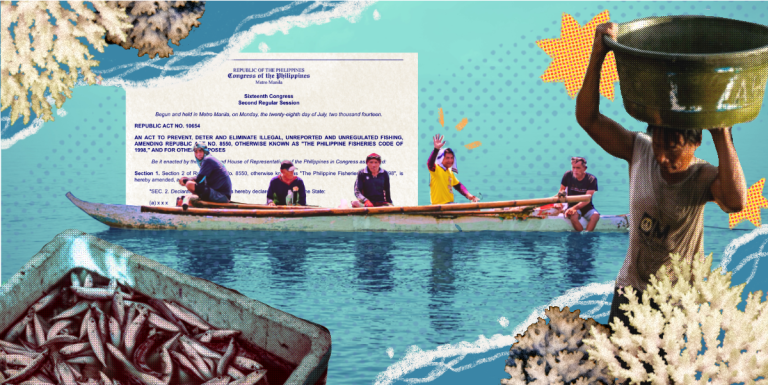

The effect on the Filipino

While this is an issue worldwide, it is worth noting that the Philippines is one of the biggest contributors to plastic pollution in oceans and other bodies of water. Publishing in Marine Pollution Bulletin, a research team from Davao Del Sur State College together with Australian institutions found an average of 3.6 plastic debris items per square meter in the riverbanks they sampled around the country. As most of the waste items collected were sachets and other types of small plastic packaging, these findings highlight the Filipino “tingi” culture of buying products in small quantities as a possible cause, reflecting that the issue is not just an environmental concern but also a likely consequence of persisting socioeconomic woes.

The study also estimates that, by the end of this year, the Philippines will rank first globally for riverine plastic emissions and oceanic plastic pollution.

The effects of such widespread plastic pollution are already trickling down to the ordinary Filipino consumer. Researchers led by Associate Professor Dr. Deo Florence Onda from the University of the Philippines’ Marine Science Institute recently sampled seafood from local markets all over the Philippines, finding that 100% of the samples tested positive for microplastics.

When ingested, microplastics can have negative impacts on one’s stomach lining and harm the digestive system as a whole. Avoiding seafood is not the answer, as researchers from Mindanao State University found that urban road dust carries microplastics as well. The plastic problem has become so bad in our country that it is in the very air we breathe.

A case for bioplastics

The world cannot just stop making and purchasing products with plastic. We can try to reduce our plastic footprint, but its practical properties simply make it impossible to eliminate from the market on a meaningful scale currently. Plastic is here to stay, but bioplastics may provide a promising alternative.

Biodegradable plastics are polymers made from renewable resources that can degrade over time but have physical properties similar enough to traditional synthetic plastics. Many of these bioplastics can be made from agro-industrial byproducts, such as waste from food, dairy, and grain, which allow them to be mass produced in a cost-effective way, much like traditional plastics.

Just last year, the Biomaterials and Environmental Engineering Laboratory at the University of the Philippines Los Baños developed bioplastics based on substances called polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are produced by fermenting bacteria collected from local bodies of water. The team collected 300 different strains of bacteria with the potential for PHA production, which allow these plastics to decompose in just one month.

Looking ahead, the project aims to scale up and start integrating PHAs in local plastic manufacturing industries. This, coupled with stronger waste management programs and further development of other plastic alternatives, might just put a dent in our country’s plastic problem.

Potential risks

While bioplastics are a promising alternative, it should still be noted that, like all new innovations, there is much to learn and validate about their functionality, stability, and ecological effects. For one, they are not entirely made of natural materials. Bioplastics have to undergo chemical processes to achieve physical qualities such as durability and flexibility that would allow them to perform like traditional plastics and be usable in a variety of production pipelines. When bioplastics degrade, these chemicals are released into the environment, and the effects on the local ecosystem are still not known.

Additionally, the study published in Sustainable Production and Consumption estimates that even partial substitution of fossil-based plastics with bioplastics will require up to one million square kilometers of land for the collection of raw materials. The resources needed for expanding bioplastic production may compete with those of food production, which could potentially pose a hurdle to food security interventions in the long run.

Microplastics are also still a concern, as bioplastics are even more prone to breaking down than traditional plastics. These particles may decompose over time, but different bioplastics do not all degrade at the same rate and not all environments are conducive to facilitating their decomposition. Additionally, since bioplastics are just now being integrated into consumer products, little is known about their effects on our health, as well as their impact on plant and animal life after they have been disposed of and start to degrade.

One plastic bag at a time

Bioplastic may have its downsides, but nearly all of the risks associated with it can be mitigated with aggressive waste management reforms. The path forward seems clear: promote further research on bioplastics, develop their potential within the country’s manufacturing sectors, and dispose of bioplastic waste in such a way that ensures it ends up somewhere conducive to decomposition.

It will take a lot of effort and changes will not happen overnight, but the slow and steady path toward bettering our plastic pollution problem is within our grasp.